By Hanan Chemlali Rosendal, Journalist / KVINFO

AMMAN, JORDAN

The sun is baking. It’s hot and it’s a little after nine o’clock. Together with Leana Islam, International Senior Programme Manager, I have traveled to Amman, Jordan, to meet with KVINFO’s long-standing partner Jordanian Women’s Union (JWU) and attend a training session they are holding for newly elected Jordanian municipal council members. I will come back to that.

We head off to the hotel where the training session will take place. Traffic is heavy, and there is a lot of pushing and overtaking. We are wearing masks as Amman still has a mask requirement in place due to the corona pandemic, and the droplets slowly collect on our upper lips. We arrive, drop our bags on a conveyor belt and go through a body scan. I am sensing a buzz of chatter. Local councillors are already mingling over coffee. We are greeted by Maysa Farraj, JWU Programme Advisor, who shows us to our seats at the back of the hall.

KVINFO’s international work takes place in countries with a pronounced lack of gender equality, and where work on gender and gender equality is an important and effective area of action with a view to create more free and equal societies. KVINFO works in Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt and Jordan in the so-called MENA region as well as in Ukraine, Armenia and Moldova.

Gender equality in legislation and in general practice is central to KVINFO’s international work. It strengthens political representation, combats violence and ensures everyone’s right to sexual freedom and health.

ACTIVE BUT SCEPTICAL

The JWU will run a total of seven training courses by the end of 2022, covering all of Jordan’s administrative units,muhafatha. Suffice to say, this has not been an easy task. A cocktail of pandemic and consequent postponement of the municipal elections themselves has put JWU in a tight corner while waiting. However, the rollout of the vaccine programme has reopened the country and JWU can finally open its doors for the first training session in the series.

I get seated in the back of the room and take my camera out of my bag, ready to snap away.

A woman stands at the front of the room in front of the big screen and asks participants to take their seats. The woman is Hala Ahed, a prominent lawyer and human rights activist. She will be teaching us the course, a role, which is quickly cemented.

She introduces herself and asks participants to stand up and gather in a circle in front of the screen where she kicks off the training with an ice-breaker– shake-and-shake exercise. On the floor, she throws different pictures with varying motifs: a house, a faucet, a family, a car. Participants are asked to bring up the image that they feel resonates with them.

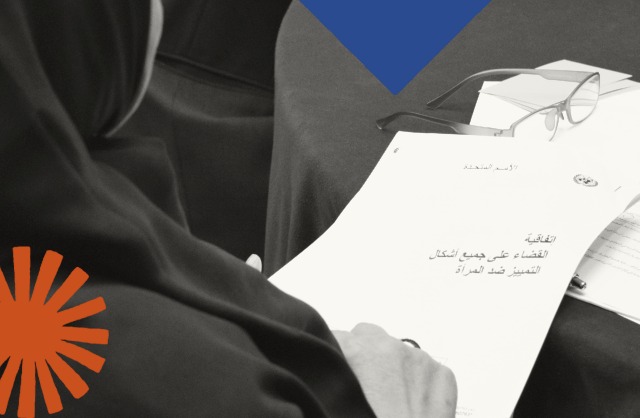

CEDAW is about the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women, and is often referred to as the “women’s constitution”. It was adopted by the UN in 1979 and ratified by the Danish Parliament in 1983. Jordan ratified CEDAW in 1992 with reservations, but it was only published in the official Gazette in 2007 – after 15 years.

The Convention contains far-reaching provisions on women’s rights to political representation, equality before the law, rights to education, economic empowerment and health, including family planning.

They are then asked at random why the image “spoke to them” and very quickly you can see that this is a group that is visibly happy to participate. This suggests that the ice was already well melted as the participants talked in the hallway over coffee, and the direction for the rest of the training session is set.

Participants are present and active. Yet, you quickly discover that there is a general skepticism among the attendees. Trainer Hala Ahed distributes questionnaires to collect participants’ expectations of the course. Something I’m also interested in delving into myself.

A BAD REPUTATION

The UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) is at the heart of the training.

I notice that one of the participants is particularly active from the start. She was also the first to take the floor during the shaking-together exercise. Her name is Yosra Alaraqdeh and she is an elected member of Amman’s municipal council.

I ask her what her expectations are for the training.

“I expect to learn more about human rights and, in particular, women’s rights and gender equality. And I expect answers to my questions regarding CEDAW,” she replies.

“In my daily work, I implement CEDAW when it is compatible with ourshariaand social norms, including our culture, but I want to get more knowledge because if it is against sharia and our culture I will not implement it.”

Sharia, which in Arabic means “the way”, is the direction that Muslims believe God has set out in the Koran, and which is followed through everyday life and religious practices; such as purity before prayer, respect for family, righteous actions and care for the poor and vulnerable.

Yosra is not the only one to raise concerns about the compatibility of CEDAW with Sharia and Jordanian culture and norms.

Several of the participants, some more active than others, voice that they are basically in favour of rights for all, but at the same time express concern about the impact of CEDAW on long-established traditions. And this is where the challenge lies for JWU and its teacher, Hala Ahed. Many of the participants eagerly recount that they have heard that CEDAW is not good for the cohesion of Jordanian society.

PUSHING CRITICAL PRECONCEPTIONS

After a lively debate among the participants, I approach the teacher, Hala Ahed, during the break. I ask her where she thinks this reluctance comes from.

She sighs and smiles.

“Teaching about CEDAW and human rights is not easy because you have to confront people’s beliefs and practices. And this shocks them.”

A male participant interrupts our conversation and asks if he can have a word with Hala Ahed for a moment. She replies that she will be there in a moment, then looks back at me and continues:

“We cannot ignore the religious beliefs of the participants, so when we talk about CEDAW and human rights in general, we actually try to interpret it through a religious lens and use terminology that the participants can relate to. People usually hear about the Convention through conservative or Islamist groups and they reject CEDAW. However, the truth is that they are not aware of what CEDAW is. They just fear that when you talk about women’s rights, it will be against family and religion and degrade the role of men.”

Hala Ahed walks over to the male participant. who wanted to talk to her. and I ask another man about his expectations of the training course. His name is Nawwaf AlMarafi and he is a municipal councillor in Tafilah in southern Jordan.

“The most important thing I expect is to have a dialog on gender equality and women’s rights. And I think it is important to highlight the difference between equality and justice, where justice is about fundamental rights and minimum standards of treatment for all individuals,” he continues:

“I am an active member of my local community alongside my position as a local councillor. We have a quota system in Jordan that guarantees seats for women, and in my city council there are four women. I think it is important to see them as equals and support their right to freedom of expression and opinions.”

The quota system Nawwaf refers to is set forth in Article 33 point B of the Law on Municipalities of 2015, which reads:

“As members of the municipal council, women are allocated at least 25 percent of the seats on the municipal council. These must be filled by the female members of the local councils within the jurisdiction of the local council that received the highest number of votes in proportion to the number of actual voters in their local council”.

Maysa Farraj, JWU’s Programme Advisor, tells me that women made up 27 percent of the elected municipal council members in the last elections in the spring of 2022.

I walk over to talk to another participant. His name is Muhammad Salem and he is a municipal councillor in Rahma and Qatar Municipality.

He talks about how, as mayor, he has seen the decline of women’s rights. He points to his two female colleagues who are refilling their coffee cups.

“I had to persuade their husbands back home to allow their wives to attend this course and reassure them that the trip was safe and that they should call home several times a day,” says Muhammad Salem.

He believes this is illustrative of the decline in women’s rights, noting:

“In our area, we have some complications in terms of women’s rights. The differences between women and men are more evident in the southern area where we come from than in the center of Amman. We have had organisations and cooperatives whose work has empowered women. However, the problem we are struggling with is that fathers or husbands were not happy with the progress and the fact that women in their families, for example, had to work with men or had less time for the family.”

Muhammad Salem explains how he actively tries to counteract men’s skepticism in his daily work.

“We lack the financial support from the government to push this agenda forward. I hope that the JWU training programme will give me the tools to break down the walls I keep encountering.”

Muhammed Salem points once again to his female colleagues:

“It has not been easy to participate in the JWU training. I had to meet with the husbands and reassure them that the women would be safe at every step. And their men still check in repeatedly throughout the day to make sure they are safe.”

I observe the rest of the training like a fly on the wall, although my camera didn’t exactly make me blend in with the wallpaper. Before long, the first day has come to an end and Hala Abed says goodbye.

THE JORDANIAN PARADOX

My colleague Leana Islam and I are back at the hotel and after yesterday’s active debates, we are expecting another eventful day. The local councillors are ready.

The trainer, Hala Ahed, handed out the CEDAW Convention in its full form the day before, and today is the day to go through all 30 articles of the Convention – one by one.

Participants are active listeners and take notes. Questions from the floor keep coming in with the same kind of concerns as yesterday, and Hala Ahed responds with zeal, energy and humor. It’s a move she told us the day before that she uses when discussions get heated. And with authoritative calm and equipped with solid facts, she manages to put a damper on the emotionally charged conversations, while respecting the views of the participants.

This morning, she turns the conversation to gender roles and unequal pay.

Despite the Jordanian royal family’s 2015 pledge to achieve gender equality by 2030, there is still a long way to go.

Hala Ahed uses the example of a woman who is an engineer. She asks the participants the question: “Shouldn’t she be paid the same as a man if she has the same seniority?” A resounding yes is said in unison.

Hala Ahed uses satirical and comical drawings in her presentation, triggering both laughter and thoughtful expressions in the room.

She highlights the stereotypical gender roles, describing the man as a provider and the woman who stays at home to cook, clean and raise a family. She also discusses the paradox that Jordan, despite having the highest number of female university graduates in the region, has the lowest female labor force participation rate in the Middle East. Only 14 percent of Jordanian workers are women, despite their high level of education, according to the UN labor organisation ILO.

Gender equality in Jordan also suffers on other parameters. As a result, the country ranks 131 out of 156 countries in the World Economic Forum’sGlobal Gender Gap Index for 2021. That makes it the 131st most unequal country out of 156. In addition, the latestArab Barometer survey from 2021 shows that the coronavirus pandemic further exacerbated the situation of Jordanian women on top of existing structural problems.

Gender equality deficiencies include gender-biased inheritance laws, stereotypical gender norms, male-dominated social expectations of what a “real man” is, with a particular focus on being the head of the family and provider. On top of the fact that many women take on caring responsibilities at home instead of pursuing a professional career.

“There is an assumption that it is the man who pays for all household chores and therefore he should be paid more. But the domestic and care-centric work that women do is not taken into account,” explains Hala Ahed, as participants nod in agreement.

As they go through the final points of CEDAW in plenary, there are fewer outbursts and interruptions and more openness and nodding from the participants.

“CEDAW IS NOT AT ALL WHAT I THOUGHT”

The course has come to an end. The atmosphere is jovial. I reach out to Yosra Alaraqdeh, who I spoke to on the first day of the course, and ask her how she has experienced the last few days.

“When I received the invitation from JWU, many people told me not to go. I was told that it was against our religious beliefs and social norms. But I insisted that I wanted to participate to see with my own eyes and hear with my own ears,” says Yosra Alaraqdeh with a serious look in her eyes.

“I was pleasantly surprised to learn that CEDAW actually does not contradict our religion and Jordanian culture at all. I will happily implement the Convention in my municipal work.”

I catch Nawwaf AlMarafi, who I also spoke to on the first day of the course, on his way out of the hall for coffee.

“I discovered that there are many misconceptions about CEDAW. What we hear on the streets is not even present in the Convention itself. We read the Convention from the official UN website and I read it thoroughly. I have a clearer understanding now. What is being said negatively about the Convention is simply not true, and I am glad to have clarified that,” he said.

Participants start packing up and getting ready for the final social activity of a late communal lunch. Before they all leave the room, I grab Muhammad Salem, who on the first day expressed a strong desire to be equipped with arguments he could use in his work as a city councillor.

“Before, I did not have a clear picture of CEDAW and almost all participants had some skeptical assumptions. They have all been disproved. Thanks to JWU, we now know that the Convention is not actually against our Islamic faith and Jordanian traditions. We went through the Convention article by article and had a good, lively discussion. We can now take all this knowledge with us in our future work,” he says with a big smile and gestures.

Lecturer Hala Ahed is left alone in the hall with JWU staff. I ask her how she thinks it went. She exhales deeply and laughs out loud.

“I feel good, but I am also tired. But I think it’s worth it. What you see is a progression from where we start to where we end. Participants are now better equipped to implement rights knowledge in their work. When I inform them about the different reservations and considerations made within the framework of CEDAW and compare with other Muslim countries and highlight how the reservations differ from country to country, the participants are extremely surprised. In this way, we can show that CEDAW is indeed compatible with our religious beliefs.”

This activity was under the project “Accelerating Gender Equality Locally in Jordan“, generously funded by theEuropean Union andthe Danish Arab Partnership Programme (DAPP).

For Hala Ahed, it has been a very demanding three days, where she has shared both facts and details and has navigated the assembly safely when the tempers were running high. She says that some of the discussions can be tough, but she is used to it.

“It hits some of their core beliefs and their fixed ideas about gender roles. When you talk to men about women’s rights, they see it as a threat to their own rights and especially their own role at home in the family. They are not willing to give up their position easily. They see themselves as the ones who have control and authority over women’s lives, choices in marriage, choice of spouses and choice of education. Men are not willing to give up this role. And it’s no wonder they are not interested in it, as that role symbolises the power they also have”, she says.

“But when you discuss gender norms and dig deep into them, it turns out that there is indeed room for change. This is not necessarily a huge immediate change in attitude, but I think the seeds have been sown and we will eventually see change. We are already seeing it today and we will see more of it in the future.”